The Russian invasion of Ukraine has swept away the illusion nurtured for over thirty years by European governments and national public opinions that war for the old continent was just a sad memory of the past or a problem that concerned other parts of the world. Today, Europe’s security is instead seriously endangered.

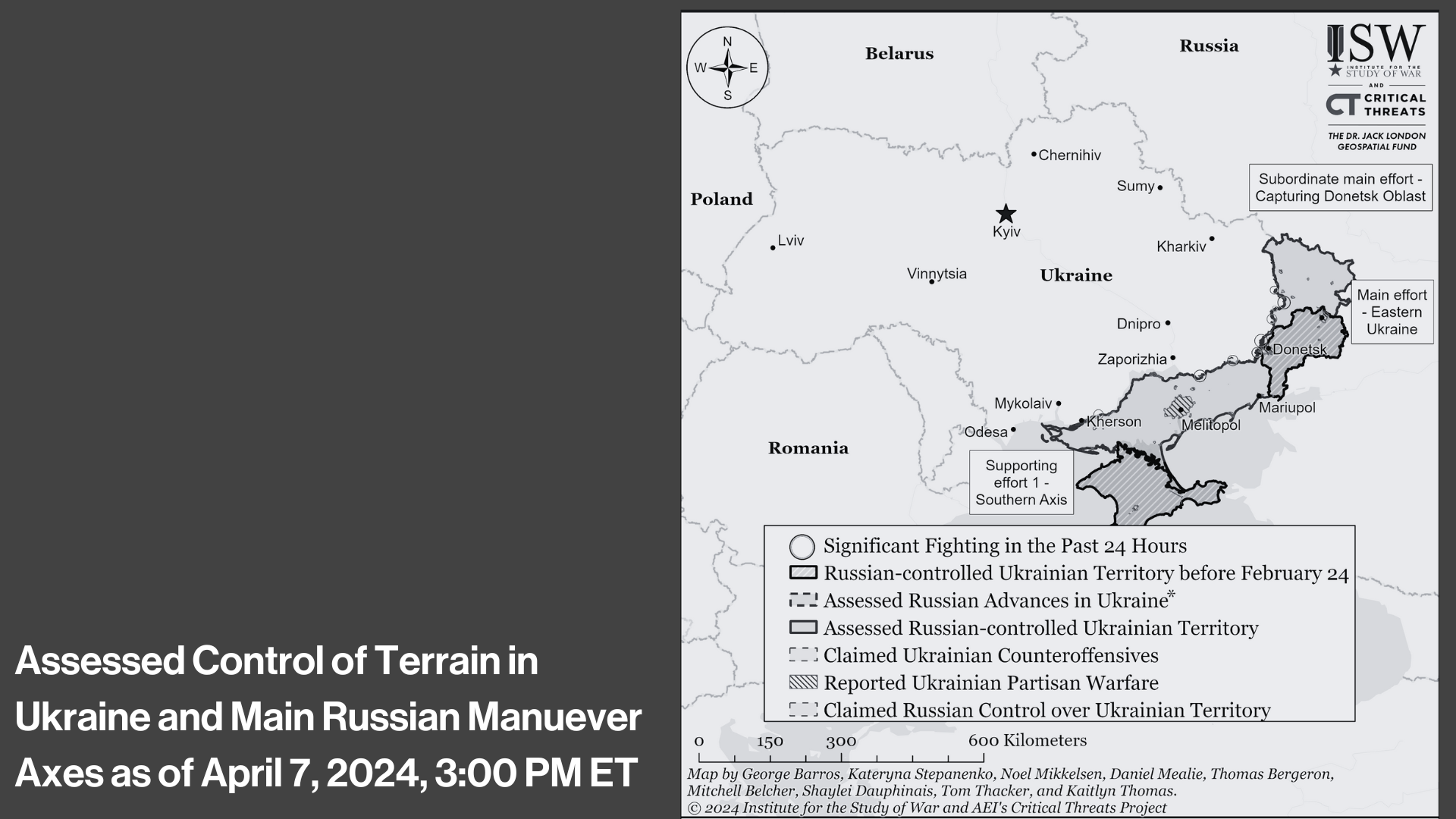

Two years after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the balance of the conflict is unfortunately very uncertain. Despite great efforts, Ukrainian resistance appears to be faltering, while Russia, bolstered by military supplies and assistance from allied autocracies, particularly Iran and China, could succeed in turning the tide of the war in its favor. The prospect of defeat calls into question Western democracies that have supported Kiev so far, and in particular the European Union, whose stability and security directly depend on the outcomes of the Russo-Ukrainian conflict.

Putin’s project for the restoration of the Russian empire does not only involve the destabilization of Ukraine and the annexation of much of its territory. Other regions where significant Russian-speaking minorities reside are already in the Kremlin’s crosshairs, particularly the Moldovan province of Transnistria, and above all, Estonia, a NATO and EU member state. It is now clear that a policy of appeasement would lead Russia to claim even more territory, resulting in the total destabilization of Europe and its common institutions. The opportune moment that the Kremlin awaits to provoke an escalation in this direction could come as early as in a few months with the potential return to the White House of Donald Trump, who is favored in the polls and has already indicated a reluctance to commit to ensuring the security of Europeans.

In light of the possible escalation of events, it is fortunate that a debate on the creation of a common defense has finally begun in public opinion, among national chancelleries, and within European institutions: there seems to be a growing perception that Europe must become capable of protecting itself without relying so heavily on the United States and by surpassing the solely national dimension of defense, which hinders the mobilization of sufficient resources for the creation of a credible deterrent force against external enemies, starting with Russia. However, there is still much confusion about what it means to create a European common defense and the ways to build it.

In the ongoing debate, various voices propose to establish a “defense union” within existing treaties. The proposals generally involve the development of an initial military capability of the Union based on some existing legal bases, such as the constructive abstention under art. 31.1 TEU for decisions concerning the common foreign and security policy, articles 46.1 and 46.2 TEU on permanent structured cooperation in defense, or through separate agreements between some governments.

Unfortunately, these are solutions that have already been unsuccessfully attempted in the past, as they are based on the “Europe à la carte” model: groups of member states engage in coordinated actions essentially of an intergovernmental nature with a veneer of “European legitimacy,” made possible only by the temporary convergence of distinct national interests and logics. Furthermore, we are not talking about truly European actions or instruments, but rather national ones, which necessarily require the approval of the Parliaments of the member states and depend almost entirely on the resources made available by each of them.

One of the major obstacles to the creation of a true European defense is indeed political in nature and concerns the practically insurmountable difficulty of developing a common European vision of foreign policy objectives starting from the attempt to harmonize 27 often divergent national interests (both political, geostrategic, and economic interests). In fact, various attempts to proceed with this method in the past have never been particularly successful (think of EU military missions in the Red Sea and the Sahel or, more recently, the introduction of PESCO for financing common projects in the defense field), nor has any of these measures served as a “springboard” to build a true European defense, because they all lacked the essential prerequisite, namely the creation of a Union foreign policy that reflects the common will matured within its institutions, particularly the Parliament and the Council. It should be added that if they have never worked in the past, today these solutions are completely inadequate given the current situation because – due to the model and assumptions on which they are based – they are no longer feasible in the face of the risk of war on European territory against a nuclear power.

Therefore, if European defense is to be taken seriously, there are no shortcuts: it is necessary to support those transfers of sovereignty at the European level that allow the Union to have its own true political autonomy, not only getting rid of the vetoes and blackmails of the member states, but also by creating the conditions to express a genuine European interest, common because it is general. This is what happened when the decision was made to truly establish the monetary union (by overcoming the European Monetary System and creating the European System of Central Banks) or, more recently, when the EU created its first instrument of fiscal policy with the Recovery Fund (managed by the Commission with debt raised on the markets by the latter on behalf of the Union). Everything else, from strengthened military cooperation to intergovernmental agreements, does not contribute to creating a European defense, but at most to maximizing the strength and resilience of national defenses through cooperation instruments in an intergovernmental dimension.

It is not denied here that, given the urgency, it is good to start doing some things with existing rules. Therefore, the acceleration in the creation of a European defense industry is welcome (also thanks to the introduction of a Commissioner with this task in the next legislature) to immediately implement the sharing of resources and the necessary know-how for the rearmament of Europe. However, the necessary condition for creating a European defense continues to be, now more than ever, a reform of the Union’s institutional framework.

This reform is now possible, and even quickly, because there would be conditions to realize it and make it operational by the end of 2025. Thanks to the work of federalists in civil society and in EU institutions, on 22 November last year, the European Parliament activated the procedure of Treaty revision to reform the Union based on an ambitious project aimed at developing a true European foreign policy and initiating military integration. The institutional reforms requested by Parliament include in particular the extension of majority voting in the Council on foreign policy and security matters and, above all, the involvement of the European Parliament in decision-making processes in these areas. This is the right direction to create a European foreign policy followed by a military union equipped with credible resources (also thanks to the development of an indispensable fiscal capacity of the Union).

What Europe does not need for its defense, however, are shortcuts and fake solutions: to believe that the Union can be equipped with its own defense by bypassing the crux of the matter, which involves essential transfers of sovereignty from the national to the European level, by empowering EU institutions and giving them the ability to decide. To believe and make believe that, all in all, this step is not so indispensable, or that it can occur by itself at a later time, would provide yet another excuse to those conservative forces at the national level, and even within the Union, that do not want to change the status quo of power in Europe and aim to bury the reform project courageously advanced by the European Parliament last November.

Faced with the urgency of moving towards a true European defense, the European Council should avoid puppet solutions and convene, as requested by Parliament, a Convention to draft a reform of the EU Treaties already in 2025. This decision would have an enormous political impact, showing the entire world and, in particular, Europe’s enemies that the Union is moving towards substantial unification and has finally begun to take care of its own security. Such a perspective would serve as a much more powerful deterrent than increasing national military spending or creating fake defense unions based on the voluntary participation of member states.