Following the victory of pro-European forces in the parliamentary elections and the confirmation of Von der Leyen as President of the Commission, some fundamental issues regarding the near future of the Union are beginning to emerge. On one hand, internal and external challenges to stability and citizens’ well-being are worsening, notably the uncertain outcome of the conflict in Ukraine and weak economic growth. This has fueled a public and political debate on the need for Europe to assume new responsibilities in the areas of defense and strategic investments. The European Commission itself could be the driving force for such a shift: President Von der Leyen has already stated before Parliament her intention to start the difficult task of building a European defense industry and promoting growth and development policies without abandoning the Green Deal and the strengthening of social cohesion. Yet, the clear need for Union reinforcement clashes with the confusion of individual national governments, concerned with maintaining consensus and unable to project solutions to their national problems into European common action.

Symbolic of this crisis is the weakness of France and Germany, whose collaboration has long been the driving force behind the integration process. In Paris, the new minority government, supported by Macronists and Republicans, is struggling to find a credible agenda and remains at the mercy of censure votes from the left (which is also fragmented) or the far-right. In Berlin, the “traffic light” coalition seems to have come to an end, with a highly unpopular Chancellor and Liberals, on the verge of extinction, still waving the specter of a government crisis. If possible, the future prospects look even darker: while in France, the parliamentary system seems paralyzed by a division into three nearly equivalent poles (left, center, and far-right), in Germany, the probable victory of the CDU-CSU in the next elections will have to come to terms with the need to form parliamentary alliances, a task made difficult by the decision of Friederich Merz – Angela Merkel’s successor – to sharply steer the party to the right, distancing it from the Socialists and the Greens. Of course, a far-right victory is not out of the question: either Marine Le Pen’s rise to the French Presidency or the entry of Alternative für Deutschland into the German government would put an end to any prospect of reviving the Union and could trigger severe disintegration processes, undoing over 70 years of European integration. Such a prospect should not be underestimated.

In this situation of severe uncertainty, Draghi’s report on competitiveness – published on the 9th of September – has come as a cold shower for European governments and institutions. The message is clear: Europe is not in crisis but in decline. The weaknesses are manifold: an inability to innovate in cutting-edge technological sectors, inefficiency in securing resources necessary for growth, and fragmentation of the capital market and banking system. The root causes of these problems lie in two structural deficits of the current Union: the lack of a political authority capable of pursuing common European interests beyond individual national vetoes and the inability to mobilize sufficient resources for innovation and economic development. Thus, divided internally and unable to make efficient decisions, the Union is losing its competitiveness compared to other global powers, primarily the United States and China. This results in a slow but steady loss of prosperity, security, and social cohesion, with serious repercussions for the stability of democratic institutions in member states.

So far, this is the diagnosis. But Draghi also offers a solution: Europe’s decline is not irreversible. The Union’s potential is still immense, and the lost path could be easily regained if certain necessary reforms are implemented, which could give a qualitative leap to the integration process. The keyword is “subsidiarity.” Europe must act united whenever necessary, which requires closer cohesion on many interdependent political fronts: public spending, environmental policies, investments in research and development, support for industry, energy supply, and foreign policy—all things that must be dealt with together from a European perspective. For this to happen, necessary institutional changes must be introduced into the Union, essentially overcoming the unanimity voting system in the Council and strengthening the role of the European Parliament and the Court of Justice in areas where they are still excluded or play a minor role. This requires a general reform of the Treaties. Alternatively, Draghi proposes simplified Treaty reforms (through the “passerelle” clauses) or, in the absence of the necessary unanimity, attempting the route of enhanced cooperation or intergovernmental agreements between groups of governments. The message is clear: Union reform is so urgent that it requires going beyond the existing constitutional framework, even at the cost of proceeding with a group of willing countries. In other words, Europe should be reorganized into multiple levels of integration, with a politically cohesive core capable of withstanding global competition.

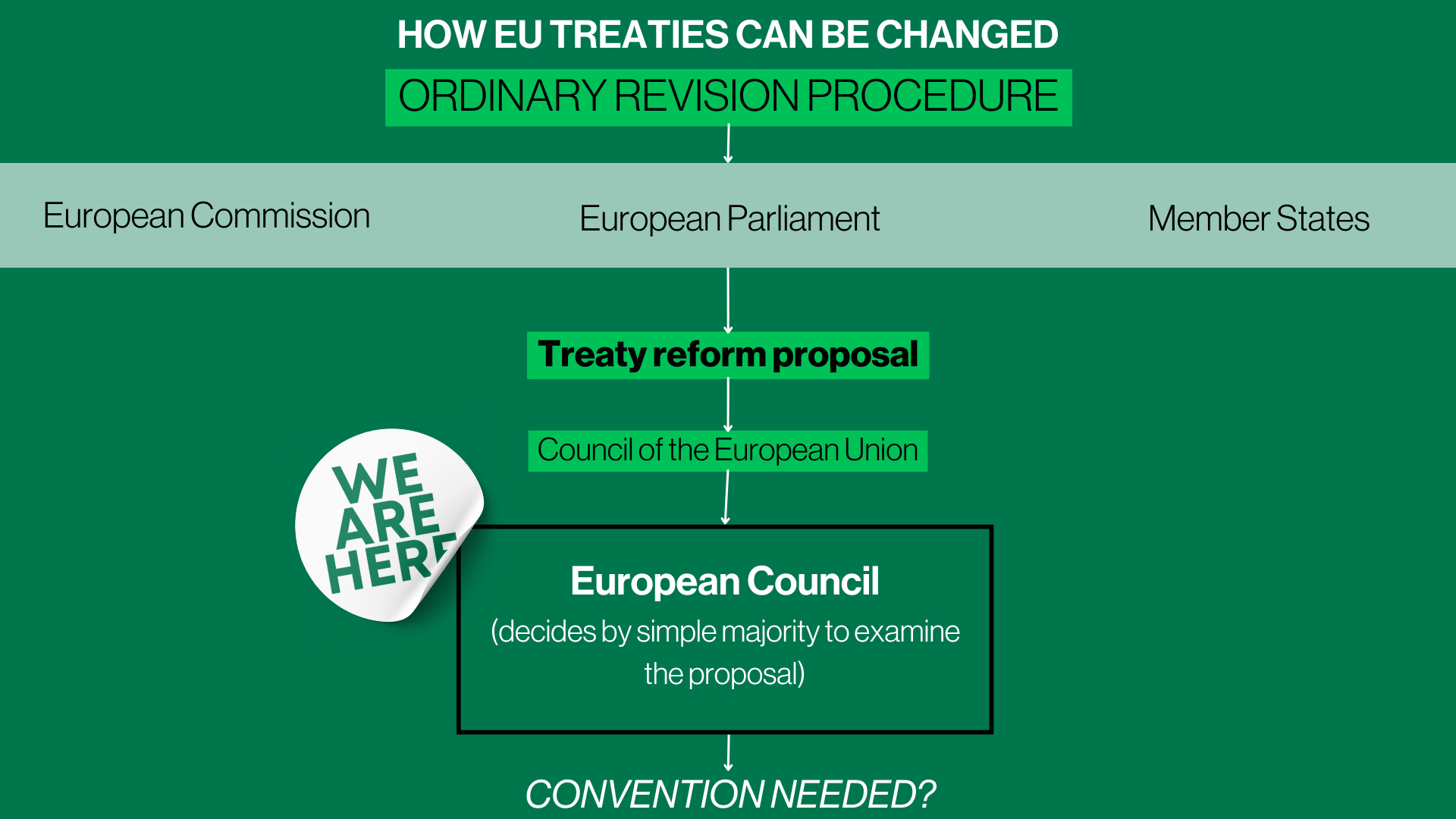

The Draghi report has been met with great attention by EU institutions and national governments, most of which, in words, have agreed with the diagnosis and what needs to be done. The question now is: who will take charge of Draghi’s plan for Union reform? Given the weakness of the Franco-German engine, a decisive role could be played by the Commission and the European Parliament. In particular, Von der Leyen, who has already taken advantage of government weaknesses to shape a more loyal College of Commissioners, should endorse Draghi’s plan and align her political priorities with the Treaty reform proposal put forward by the European Parliament last November. This project, which includes many of the institutional reforms requested by Draghi—starting with the elimination of unanimous voting—has been stuck on the table of governments for months. Renewed support from the Parliament and the new Commission for the Treaty revision project would be crucial in pushing the European Council to convene a Convention by a simple majority and thus opening the long-awaited reform process to put the Union in a position to defend its interests and values in an increasingly competitive and brutal international context.